This essay was originally published in Stat Significant, a free weekly newsletter featuring data-centric essays about movies, music and TV.

["Say Anything" (1989). Credit: 20th Century Studios]

["Say Anything" (1989). Credit: 20th Century Studios]

Intro: Spotify's Comfort Food DJ

I recently tried Spotify's new DJ feature in which an AI bot curates personalized listening sessions, introducing songs while explaining the intention behind its selections (much like a real-life disc jockey). Every four or five pieces, the bot interjects to set up its next block of music, ascribing a theme to these upcoming works. Here are some of my example introductions:

-

"Next, we're gonna play some of your favorites from 2016."

-

"Here are some of your favorite indie rock songs from the 2010s."

-

"Up next, we have some music inspired by your love of 2000s hip-hop."

With each DJ interlude, something became increasingly clear: my music taste had barely changed over the course of a decade. Armed with full knowledge of my musical interests, this AI agent had pinpointed my musical paralysis, packaging an algorithmic echo chamber of 2010s indie rock, 2000s pop, Bo Burnham, Blink-182, and Bruce Springsteen. Had my music taste stagnated?

This minor existential tailspin sent me down a Google rabbit hole — I began frantically researching music paralysis and the science of sonic preference. Was this phenomenon of my own doing or a natural product of aging? Fortunately, the topic of song stagnation has been well-researched, aided by the robust datasets of streaming services.

So today, we'll explore how our relationship to music changes with age and the developmental phenomena driving our forever-shifting cultural tastes.

When Do We Stop Finding New Music?

Open-earedness refers to an individual's desire and ability to listen and consider different sounds and musical styling. Research has shown that adolescents exhibit higher levels of open-earedness, with a greater willingness to explore and appreciate diverse musical genres. During these years of sonic exploration, music gets wrapped up in the emotion and identity formation of youth; as a result, the songs of our childhood prove wildly influential over our lifelong music tastes.

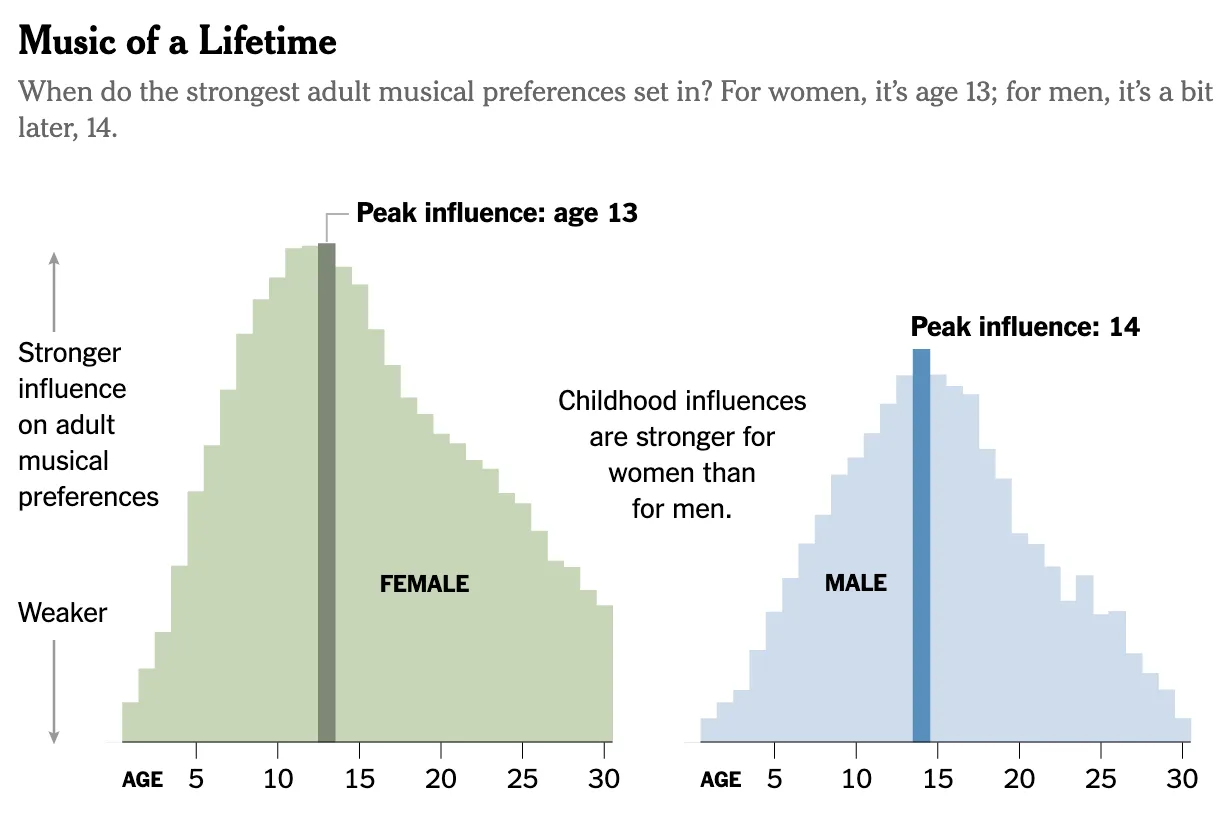

A New York Times analysis of Spotify data revealed that our most-played songs often stem from our teenage years, particularly between the ages of 13 and 16.

[Credit: The New York Times]

[Credit: The New York Times]

This finding has personal resonance, as I remember my cultural preferences being easily influenced during my pre-teen and early teenage years. For instance, I was twelve when Green Day released their landmark "American Idiot" album, a work that proved monumental in my relationship to music. Listening to the album's titular track felt like a supreme act of rebellion (for a twelve-year-old suburbanite). I was entranced by this song's iconoclastic spirit — could they actually say, "f**k America?"

["American Idiot" music video: Credit: Reprise Records]

["American Idiot" music video: Credit: Reprise Records]

But "American Idiot" wasn't a true act of revolution. In fact, the album was produced and promoted by a multinational conglomerate with the intent of packaging seemingly transgressive pop-punk acts for my exact demographic. How was I so thoroughly seduced by this song? And yet, to this day, my visceral reaction to “American Idiot” is still one of euphoria, despite my cynicism. I guess I have no choice but to love this song forever (thanks to pre-teen me).

Indeed, YouGov survey data indicates a strong bias toward music from our teenage years, a phenomenon that is consistent across generations. Every cohort believes that music was "better back in my day."

[Credit: YouGov]

[Credit: YouGov]

Ultimately, cultural preferences are subject to generational relativism, heavily rooted in the media of our adolescence. It's strange how much your 13-year-old self defines your lifelong artistic tastes. At this age, we're unable to drive, vote, drink alcohol, or pay taxes, yet we're old enough to cultivate enduring musical preferences.

The pervasive nature of music paralysis across generations suggests that the phenomenon's roots go beyond technology, likely stemming from developmental factors. So what changes as we age, and when does open-eardness decline?

Survey research from European streaming service Deezer indicates that music discovery peaks at 24, with survey respondents reporting increased variety in their music rotation during this time. However, after this age, our ability to keep up with music trends typically declines, with respondents reporting significantly lower levels of discovery in their early thirties. Ultimately, the Deezer study pinpoints 31 as the age when musical tastes start to stagnate.

These findings have been replicated across numerous analyses, including a study of Spotify user data from 2014. Produced from Spotify's internal dataset, this research explores how tastes deviate from the mainstream with age. In this analysis, a contemporary pop star like Dua Lipa would score a one (the most popular), and an artist further out of the zeitgeist like Led Zeppelin would rank somewhere in the 200s. The resulting visual is unnerving as we observe our cultural preferences (quite literally) spiral away from the mainstream as we grow older.

[Credit: Skynet & Ebert]

[Credit: Skynet & Ebert]

This study identifies 33 as the tipping point for sonic stagnation, an age where artistic taste calcifies, increasingly deviating from contemporary works. But wait, there's more. Spotify data indicates that parents stray from the mainstream at an accelerated rate compared to empty nesters — a sort of "parent tax" on one's cultural relevancy.

[Credit: Skynet & Ebert]

[Credit: Skynet & Ebert]

But this stagnation goes beyond the popularity of our music selections; it's also the diversity across these works. From 30 onward, we listen to more music outside the mainstream and sample fewer artists during streaming sessions.

[Credit: Music Machinery]

[Credit: Music Machinery]

Reading these studies proved an existential body blow because I am 31, apparently on the precipice of becoming a musical dinosaur. I like to think I'm special — that my high-minded dedication to culture makes me an exceptionally unique snowflake — but apparently I'm just like everybody else. I turned 30, and now I'm in a musical rut, content to have an AI bot DJ pacify me with the songs of my youth.

I used to spend hours researching artists, scrutinizing my CD purchases, and, later, my iTunes selections. Musical exploration was an activity in and of itself; songs were more than background noise. Now, I'm stuck listening to James Blunt's "You're Beautiful" for the 1,000th time. What happened to me?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content? Subscribe to Stat Significant for free, and receive new data essays every week.

Why Do We Stop Finding New Music?

Music paralysis is the product of both biological trends and practical constraints. Deezer survey respondents who identified as being "in a musical rut" cited numerous day-to-day limitations as cause for their stagnation, with the top three reasons being:

-

Overwhelmed by the amount of choice available: 19 percent

-

Having a demanding job: 16 percent

-

Caring for young children: 11 percent

This first point regarding the paradox of choice is especially intriguing and would speak to streaming as some sort of societal ill, bombarding us with boundless content. It's easy to condemn Spotify for giving us too many options, but this complaint is likely emblematic of a broader developmental shift.

Context is critical to cultural discovery. An extensive cross-sectional study regarding musical attitudes and preferences from adolescence through middle age found that our relationship with music drastically changes over time. Surveying over 250,000 individuals, this study found:

-

The degree of importance attributed to music declines with age, even though adults still consider music important.

-

Young people listen to music significantly more than middle-aged adults.

-

Young people listen to music in a wide variety of contexts and settings, whereas adults listen to music primarily in private contexts.

The issue of music discovery does not originate from infinite choice; instead, this problem likely stems from decreased listenership and a waning commitment to exploration. Spending two hours a day combing through iTunes (now Spotify) is impractical. My priorities have changed, my emotional connection to music has changed, and I simply just don't have the time.

Indeed, this same cross-sectional study revealed that musical preferences are closely related to trends in psychosocial development. In this survey, researchers investigated how tastes vary across five dimensions as we age: intensity, contemporaneous, unpretentiousness, sophistication, and mellowness. The data they collected demonstrates a universality to our forever-changing relationship with music — it's natural to expect a progression in our preferences.

[Credit: “Music Through the Ages”]

[Credit: “Music Through the Ages”]

It's tempting to despair over these results, to accept changing cultural attitudes and the phenomenon of music paralysis as a predetermined truth. At the same time, stagnation is not a certainty. Research suggests that open-eardness and the discovery of new songs can be cultivated. Finding new music is a challenge, but it is achievable with dedicated time and effort. If we avoid the warm complacency of nostalgia, we can recapture our flare for music discovery.

Final Thoughts: Music's Optimal Stopping Problem

[High Fidelity (2000). Credit: Buena Vista Pictures]

[High Fidelity (2000). Credit: Buena Vista Pictures]

My father "likes what he likes": Bruce Springsteen, Field of Dreams, The Washington Nationals, and consistently reminding me that Fleetwood Mac's Rumours was made after its bandmates divorced one another. Whenever I point out my dad's stubborn habits, he'll look at me, smile, and quote the immortal wisdom of Popeye: "I am what I am."

When I was younger, I strongly disliked this rationale. Surely, there is no fixed version of who we are. Humans are constantly evolving — perpetually engaged in self-discovery. But maybe this isn't the case for all facets of life.

The explore-exploit trade-off refers to the dilemma between seeking new information (exploring) and optimizing decisions based on known information (exploiting). Some examples of the explore-exploit trade-off include:

-

Restaurant selection: Do you find a new restaurant or return to your old haunts?

-

Movies: Do you watch something new or re-watch an all-time favorite?

-

Career: Should you keep your current job or look for a new one?

In the case of music discovery, exploring would consist of finding new songs and subgenres, while exploiting would entail listening to already-beloved tunes.

The explore-exploit trade-off and an adjacent decision-making puzzle known as the optimal-stopping problem have prompted extensive research and the coining of a shortcut known as the 37 percent rule. This heuristic suggests we spend the first 37 percent of available search time exploring our options before settling on a preferred solution or selection.

In the case of musical preference, the current American lifespan averages 80 years; when we multiply this figure by 37 percent we get 30 years — coincidentally, the age at which music tastes stagnate. This back-of-the-envelope math could be interpreted in two ways:

-

I am going crazy: I see numbers and symbols that don't mean anything. The 37 percent rule is a vague heuristic that may not even apply to this case, and I am perceiving order from true randomness.

-

Thirty is our optimal stopping point: Despite the 37 percent rule being a highly generalized heuristic, there is some merit to doubling down on our favorites after a sustained period of searching — a phenomenon that appears to be our default state. We spend 30 years exploring new music, and once we've sampled enough works, we reach an optimal stopping point, comfortable with our rotation of artists and songs.

Maybe music paralysis is a feature, not a bug. Running on a never-ending treadmill of cultural exploration may be a recipe for discontent. There is nothing inherently wrong with "liking what you like." Is it my waning music discovery that's making me unhappy or the fact that I've yet to accept this reality?

Perhaps I should forsake sonic exploration and exploit my love of "American Idiot," 2010s indie rock, 2000s pop, Bo Burnham, Blink-182, and Bruce Springsteen, content to live in an algorithmic echo chamber curated by DJ — my new AI savior.

If you’d like to read more data-centric essays about movies, music, and TV, take a look at my newsletter, Stat Significant.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]